How Much of This is True? And other questions authors dread

Sometimes the question comes in other forms. What gave rise to the novel? What was the inspiration for your story? Is it autobiographical?

I am as guilty of wanting answers to those questions as any reader. I’ve just finished Adam Haslett’s heartbreakingly beautiful novel, Imagine Me Gone, and I can not help wondering whether the novel’s brilliance is in part born out of personal experience with crippling depression.

I read Imagine Me Gone at our place in the mountains. I sat beside a lake, oblivious to the sun burning my back and the odd little black beetles stinging my calves. It was a novel that sucked me into its psychology, drowned me in one family’s despair and unfailing love, and felled me with its humor, its intelligence, and its vision. It released me two days later furious, devastated, moved, and envious. As only the finest literature can do, it had altered me. Does it matter how much of it is “true?” It matters only in that whatever tragedies in the author’s life gave rise to it, we can be grateful as readers that he had the courage and tenacity to turn those experiences into art.

As Stephanie Harrison writes in BookPage: “Imagine Me Gone is immensely personal and private, yet feels universal and ultimately essential in its scope. The end result is a book you do not read so much as feel, deeply and intensely, in the very marrow of your bones.”

When literary realism succeeds, it feels like life. When it doesn’t, it feels contrived. In my experience, this is the case whether the events that inspired the fiction happened or not. I have often become burdened by small details from my own experience that I try to manhandle into an evolving fiction. My own nostalgia insists this gem of an anecdote or detail belongs. But often, it’s not the right thing; it belonged in my life, but not in the fabrication it inspired. The opposite is of course also true: sometimes life delivers up a line of dialog, or a situation or detail that can not be matched by invention. When there is a risk of offense, though, sometime we writers have to suck it up and settle for an inferior construction of our imaginations.

In an interview for American Short Fiction, the lovely Rachel Howell asked me how much of my own life, and past, informed my work, and how I managed to keep narrative distance while very much writing what I know.

I responded that I often begin with the low-hanging fruit: places I’ve lived, my own experiences, emotions, memories, observations, friends, family. Stories people tell me or that I read in the newspaper. Conversations I overhear in restaurants. That’s the raw material. And often, the initial attempt to get this material onto the page is done in a voice close to my own.

But once I begin to shape the material into something resembling a story, once characters emerge, the voice, or voices, if there is more than one narrator, will necessarily be transformed. Even though some of what happened to the narrator happened to me, the voice is no longer mine—it’s one that has emerged in the service of the story over years of revision. The story is not my life but a collection of sentences deliberately, fictionally shaped to deliver an emotional truth that becomes clear only as the story unfolds.

In the last year and a half since the book came out, I’ve spoken and written at length in essays and interviews about the features of my own life that gave rise to the novel. All that I’ve said and written on the topic is true. Is it the whole truth? No story ever is.

The Interruption of Best-Laid Plans

Commencement Address, June 5, 2016, Flintridge Sacred Heart Academy

Thank you, Sister Katherine Jean, for that lovely introduction, and thank you Sister Celeste, Sister Carolyn, esteemed faculty, proud parents, and most of all, radiant graduates of the Flintridge class of 2016.

What an incredible honor to be here today to recognize not only your achievements, but your supreme effort. You have challenged your intellects; you have invested in friendships that will last you a lifetime; you have been supported by the boundless love of your families and the brilliance and devotion of your teachers. In turn, each of you has blessed those gathered here in your honor with immeasurable, and particular, joy. We celebrate you.

In thinking about what I might say today, I tried to find the speech I gave when I stood on this stage exactly thirty-three years ago. I couldn’t find a copy of that valedictory address, but I do remember that June day in 1983 clearly, and I know that during my time at Flintridge, I had learned a few things:

In four years of early morning swim practices, and at meets in which Coach Betsy Sauer invariably put me in the 500-meter freestyle event, I learned that if you just keep kicking, you will survive that horrific twenty laps and reach the end of the race, even if, without exception, the best you can do is finish last.

I had learned that if you complete your Sunday shift working the front desk of the main building and find that you have tossed your retainer out with your lunch, you can retrieve it by diving vigorously in the dumpster out front, hoping none of your friends will see you.

I knew from Katy Sadler’s phenomenal AP US History course that the story of our country fascinated me, and that I wanted to continue that study in college. From Sister Katherine Jean, I had learned that I loved language, and that literature was the finest way to immerse oneself in the imagination of others. And after four years in Marilyn Hobson’s classroom, I knew how to conjugate my French verbs.

I knew that I had forged profound friendships, as you have, friendships that had sustained me in both joyful and difficult times. Through the Student Christian Action Movement, I had learned that service, like literature, was a gateway to empathy and compassion. And working on the ASB Board alongside five exceedingly competent peers, some of whom are here today, I knew that when it came to leadership, there was nothing a boy could do that we could not do better.

Then I went off to college. Some of what I had learned, I remembered, and some of it, I forgot. You have been given many gifts here at Flintridge—but if you’re anything like me, you will not understand the full value of those gifts until you have misplaced them, then stumbled upon them again, as you walk through the journey we call life.

That journey will not take a straight and easy path. It will include disappointments and despair. It will be marked by missteps, wrong turns, backtracking, stalling, and engine failures. What I have learned during my own journey over the three decades since I left this hill, and what I hope to share with you today, is that it is often the breakdown that leads to the breakthrough, it is the misstep that sets us on the right road, it is the interruption of our best-laid plans that clears the path to our destinies.

After I left here when I was seventeen, I continued my study of French in college. My plan was to spend my junior year abroad, living in Paris with a French family, studying at the Sorbonne, speaking not a word of English, and, most importantly, drinking coffee in sidewalk cafés. But when at the end of my sophomore year, I interviewed for the Stanford-in-Paris program and members of the French faculty started firing questions at me, I panicked, forgot not only the conjugations Madame Hobson had drilled into us so diligently, but the entirety of my French vocabulary as well.

I was not accepted into the Stanford-in-Paris program, and I was devastated. But I was also determined. So I saved some money, stopped out for a quarter, and went to Paris anyway. I found an apartment, took a few French classes, and indeed, sat in sidewalk cafés. I traveled the continent on weekends, read novels, and took notes. In January, instead of returning to college as planned, I moved to London, got a job in an office, read more novels, and took more notes.

My journals from that year became the germ of a novel of my own that I would begin to write twenty years later. The seeds of the obsession with words and stories that would ultimately shape my life had been planted. But it was going to be awhile until I remembered to water those seeds, and when I graduated from Stanford two years later, I had lined up a job not in publishing or journalism, but in—of all things—investment banking.

There is nothing wrong with investment banking, but there was everything wrong with it for me. I was a history major; I had not completed a math course since Algebra II here as a junior; I had dropped calculus, and gotten a “C” in financial accounting, the only “C” of my academic career. How had I persuaded Morgan Stanley to hire me as a financial analyst, and more critically, how had I persuaded myself Wall Street was where I belonged?

Theodore Roosevelt once famously said that comparison is the thief of joy. That spring of my senior year, I had watched my Stanford classmates land high-paying jobs with tech companies, management consultants, and banks, and I had made a choice certain to make me miserable. I had forgotten what I knew so well, here at Flintridge, that a safer measure of success than money or prestige was integrity, faith in my own intuition, and pursuit of the truth of my own life.

Yet I cashed my signing bonus from Morgan Stanley, bought four suits at Macy’s, and found a place to live in Manhattan. Then I stood by as my two roommates, who had cleverly avoided lining up gainful employment, decided to make excellent use of their Stanford degrees by moving to Hawaii, getting jobs as cocktail waitresses, then backpacking around the world.

I was faced with an existential dilemma: Should I join them, or should I start the job? I did what I still do in a crisis, existential or otherwise: I called my mother.

She listened to my predicament, and with the breathless conviction that can only be earned by having been a single mother who worked two jobs and made countless sacrifices to secure her three children’s futures, she said: “Take the trip.” And she promised to make my student loan payments for as long as I was away.

She could not afford those loan payments, nor could she afford to send me to Flintridge, or Stanford, in the first place. Somehow, she had faith that it would all work out, and it did. Like my father’s faith in my ability to do anything I set my mind to, and like the unconditional love of your families, gathered here today, my mother’s quiet courage made my own path possible.

I was away for two years, working in Hawaii and Australia, backpacking across Southeast Asia, trekking solo in the Himalayas, taking trains across India, job-hunting, unsuccessfully, in Hong Kong—and along the way, taking notes. I was often afraid I was wasting my time, but the left turn that sent me to Maui, instead of Manhattan, ultimately set me a step closer to becoming a writer.

Still, it was going to take awhile. When I returned home, I had no car, no money, and no place to live, so after a few false starts, I found a job—no, not in publishing or journalism—but in a start-up that in the years before they so famously brought down the world’s financial system, made risk management software for the derivatives traders of commercial and investment banks. Finance—again.

Shortly after I was hired, my boss, the VP of marketing, quit, and I took up where he left off, running the marketing department for five years, and helping to write the prospectus for our Initial Public Offering when I was eight months pregnant with my first child.

How did I master the esoteric financial and software modelling behind our complex product? I didn’t. I faked it. And what I came to understand is that while it is often necessary to pay your rent or put food on the table, faking it, whether in work, art, or love, will in the long run starve your soul.

My children were the happy interruption that drew me out of a career I might have stayed in indefinitely, even though it wasn’t my calling. After my second child was born, I quit to stay home and raise my kids and finally, to write. I was thirty-three when I signed up for my first writing class. A year later, I entered the MFA program at San Francisco State. I had two more kids. It took me seven years to earn a Masters in Fine Arts in Creative Writing, taking one class each semester. It took me five years to write and publish a first short story, inspired by my time in Australia.

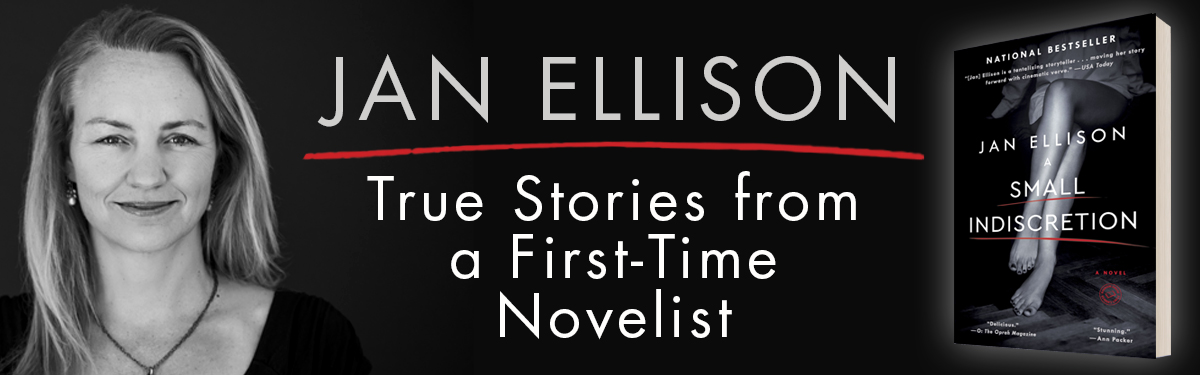

I revised that story at least one-hundred times, and before it finally found a home, it was rejected by twenty-seven literary journals. (But who’s counting?) Then it went on to win a prize that jumpstarted my writing career and that many years later, paved the way for the sale of my novel in just one day to Random House.

But no award or recognition will immunize you against self-doubt, and I wondered: was the rejection I’d encountered the true measure of my talent, or the prize? The one-star, or the five-star reviews? The quick sale to a publisher, or the initially sluggish hardcover sales? The answer, I have learned, is neither. Life is not like swimming the 500-meter freestyle. It is not a time to beat or a race to win or a medal to hang around your neck. In life, a better goal than winning is to keep swimming with an open heart and an open mind toward your own truth.

I am reminded of a quote from the incomparable Martha Graham, credited with having invented modern dance in America, words that are true not only of art, but of all human endeavor:

There is a vitality, a life force, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and there is only one of you in all time. This expression is unique, and if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium; and it will be lost. The world will not have it.

It is not your business to determine how good it is, nor how it compares with other expression. It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open. [i]

What ultimately mattered more than the success or failure of my book was the outpouring of support I received from family and friends, including my classmates here at Flintridge. A group of those classmates traveled North to attend my book launch in San Francisco. They bought copies for their book clubs and arranged readings at bookstores here in Southern California— attended by Flintridge teachers, administrators and friends. Their loyalty touched me deeply, and drove home for me your theme here this year, put so well by St. Thomas Aquinas: “There is nothing on earth more to be prized than true friendship.”

Three years ago, my husband’s best friend and business partner died of cancer. They had worked side by side for twenty-five years, and his death was an immeasurable loss. At his memorial service, his wife read a passage that has become a touchstone for my husband and me, the words we offer each other when one of us loses heart, loses faith, closes the channel and retreats. Or when we are stingy, rather than generous, with our love. When we begin to take our days, or our children, or each other, for granted. I’d like to close by sharing with you those words:

Life is fragile, use it roughly. Wrest from it all you can. Love in it what you’ve got . . . Because death, it turns out, does not respect our plans for personal improvement. It does not rank us as human beings or decide who’s deserving of its favors and who isn’t . . .

The only person to whom the universe is benevolent is the person who squeezes all life into a chestnut in his palm and squeezes its juice . . . The transience of our lives is an argument for loving—for loving children, experiences, tragedies, destinies we may not have thought intended for us, but which we can make our glory.[ii]

Graduates, you have used life roughly, here on this hill, and I know you will continue to do so as you go forth to forget, and then remember, all that you have learned here at Flintridge, and to build beautiful lives of faith, integrity and truth.

Congratulations, and God Bless You.

The Helicopter Parenting of Baby Book

“My agent pointed out ever so gently that while he was away from his email over the weekend, I’d sent him no fewer than 23 individual messages.”

When I sold my novel to Random House, I assumed publishing a book would be a more or less reptilian exercise: You plant the egg (the novel) in a nice warm place (a top publishing house), and it hatches and raises itself. But it turns out to be a lot more like raising an infant, only not as cuddly. Not softened by a flood of oxytocin. Not cushioned by a love that grows every single day.

When our first child, now a freshman in college, was six months old, I hired a nanny to take care of him while I worked half-time from home. I prepared a document entitled “Taking Care of Baby,” which I came across recently, two pages of single-spaced typed directives for our unsuspecting new hire, who is instructed to:

- “make sure the diaper area is very dry before putting on a new diaper”

- “put baby down in crib on back, with security blanket to hold, then check after 10 minutes to make sure security blanket is not covering face”

- “place baby under a black and white mobile several times per day for stimulation.”

And for a walk in cold weather, Nanny must:

“dress baby in socks, blue hat, blue mittens, sweatshirt and blanket.”

The woman upon whom this document was thrust had already raised four children of her own. She ought to have been typing up instructions for me.

Fortunately for my kids, I ran out of fuel for that kind of helicopter parenting a long time ago. But that doesn’t mean I’ve stopped hovering. To paraphrase our eldest daughter: “You know how some parents derive their sense of self-worth from the success of their kids? Well, you don’t do that with us. But you definitely do it with your book.”

My book had what my publicist called “a slower ramp.” It received great trade reviews from Kirkus and Booklist, was in a feature in Cosmo, and had generous blurbs from other authors, but the day it was published, it did not yet have a single press review. I was advised not to worry. I was told to focus on writing my next book—sound advice that I systematically ignored.

Partly, this was the result of an obsessive-compulsive nature. Partly, it was because in my twenties, I’d spent five years running marketing for a Silicon Valley start-up and helped take the company public. Random House was working hard on my behalf, but when it became clear the book was not going to magically transport itself onto the New York Times bestseller list, my maternal marketing instincts kicked in. Work on the next novel stalled in favor of the feeding and care of the first, and I started working 14-hour days marketing the book. I was on West Coast time, three hours behind, but by the time New York publishing began its day, I had typically already been at my desk sending emails for at least an hour.

Random House publicity ended up doing a stellar job—securing a rave review that appeared on the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle’s book section, an Editor’s pick from Oprah, prominent radio spots, and essay placements in both the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. When their campaign wrapped up after 6 weeks, though, I was still in overdrive, and I thought they should be, too. But that’s not how it works.

My agent, like my nanny all those years ago, was patient, and kind, and honest in guiding me through the realities. He helped me understand that a publishing house can only market a single book for a short time before it must move on to other books, and nothing I could do was going to change that. One Monday morning, he pointed out ever so gently that while he was away from his email over the weekend, I’d sent him no fewer than 23 individual messages.

Clearly, it was time to settle down. But I couldn’t. Or wouldn’t.

I learned a lot. I could (I might) teach a class on what not to do as a first-time author: Don’t waste your time stalking Goodreads reviews, and Amazon rankings, and Google search results. Don’t send so many emails that you exceed your daily limit and turn your messages to SPAM. Don’t raise your voice with your publicist, your agent, your editor or your marketing team. Don’t sweat the small stuff. But don’t wait until the last minute to build a good web site, either. Don’t fail to nail down an elevator pitch until a year after your book has come out. Don’t neglect to turn on Google Analytics. Don’t be surprised when you find you need not only a Facebook Author Page, but Facebook Insights, a Facebook Pixel, and Facebook’s Ad Manager and Power Editor. Do not resist Amazon Associates, MailChimp, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, LinkedIn, YouTube.

Do not wait to expand your vocabulary to include terms like landing page, mobile discovery, audio clip, bookplate, illegal download, metadata, keywords, thumbnails, blogging. Do not hesitate to call in reinforcements—like your father. Especially if, like mine, he happens to be a graphic designer, marketing consultant and a writer himself: www.etellison.com. Do not expect to spend every evening with your family. Do not think you will survive two dozen book club gatherings and 30 events without someone calling your young protagonist “icky.” Do not show up for your first reading unprepared. Do not forget your fancy new pen. Do not expect your publisher to take care of everything. Do not try to take care of everything yourself.

In the end, have all these efforts mattered? I think they’ve mattered in helping build personal relationships with independent bookstores and with readers, and they’ve helped the book find its way into the hands of people to whom it has meant something. Beyond that, the effort mattered in the way it mattered to me that my son’s imagination was stimulated by a black and white mobile, and that he was bundled up in his socks, his blue hat, and his blue mittens when it was cold outside. It mattered to me to know that I had done my best—and the only way to make all of it matter less was to allow time to pass, and to ultimately turn my attention to a new baby, or a new book.

Will I have calmed down when it comes time to publish a second, a third, a fourth book? Will I have traded helicopter parenting for parenting on-demand, as I have with my actual children? I hope so. I hope that like our fourth child, who just turned twelve, my next books will dress themselves from an early age and make their own breakfasts. They will remind me to put my cell phone away when it’s time to get off a chairlift. They will even take it upon themselves to make bread when the bananas go brown.

Writing sex scenes when you’re a mother of teenagers

“How does it feel to know that your teenagers will now know their mother has a sexual imagination?”

This was perhaps the most provocative of the questions that came my way after A Small Indiscretion was published, and it threw me. In a review in Bustle, Rebecca Kelly calls the sex in A Small Indiscretion “decidedly un-erotic, even uncomfortable or cringe-worthy.” Is this, then, what my kids might assume constitutes their mother’s sexual imagination?

My 19-year old son asked to read the book when the Advance Reader Editions arrived. It sat on his nightstand for a long time, bookmarked at page 30. Every so often I’d sneak in his room to see if he’d progressed, but the book mark never moved. I finally told him he shouldn’t feel any pressure to finish the book if he didn’t want to, and he seemed relieved. He said maybe it was a little too character driven for him. Only later did he admit the truth. The son character, Robbie, plays the piano and is a good swimmer, enough similarity to make my son uncomfortable. The novel is written in the form of a letter from a mother to her son, which certainly must have contributed to my son’s unease.

The book did time on my 17-year-old daughter’s nightstand, too. The bookmark got stuck about half way through. “It’s not that it’s not good or anything,” she said. “It’s just…I mean…I know it’s not you, but I know you, so I can see where your ideas come from, and it’s just kind of weird.” As far as I know, neither one of them ever got to the sex scenes, un-sexy or otherwise, which is a relief. My other two kids, daughters aged 11 and 14, are young enough I’ve simply told them they’ll have to wait.

In the writing of the book, I always knew that the narrator, Annie Black, was only writing for herself, that she would no more share her sexual experiences with her child than I would. I knew her confession would never find its way into anyone else’s hands, and as I wrote, I had to persuade myself the same was true of my novel, that I would be the only person to read it. I locked myself in the room of my mind and followed the characters wherever they went, even into bedrooms in which they undressed. But I was never uncomfortable writing the sex scenes, not only because they aren’t explicit, but because it was the underlying emotional truth I was focused on describing, not the sex for its own sake.

The Bustle review goes on to say that the un-sexy sex scenes have a “gritty emotional realism,” that they are there “to intrigue, not titillate.” I hope this is true; as critical as at least one of them is to the plot, the sex scenes, to me, felt minor relative to the scope of the story. So I was taken aback when again and again, readers called the sex out. My husband read the book for the first time and pronounced it “a sexy page-turner.” The jacket copy my editor wrote included the term “sexual desire,” and reviews referred to “sexual antics” and “sexual confusion.” I ought to have been prepared for this, perhaps, but I wasn’t.

When I published my first short story, The Company of Men, which went on to win an O. Henry Prize, I remember a moment of panic when I realized my mother-in-law was likely to read it. There isn’t any graphic sex in that story, either, and yet I felt ashamed of paragraphs like this one:

“And beyond that, where my husband’s arm had been, was only the back of the couch. There was no sign of the formidable wrist, the sturdy thumb, the callused, well-loved palm. There was no further sign of my husband in the room at all. I was on my own in the company of men with the makings of a straight in my hand, aces high. Desire was thumping in my chest and the instinct to win, to go forward with abandon, was shooting through me, across the back of my neck and down between my legs . . . Then all at once there was a knee pressed purposefully against my thigh beneath the table.”

The protagonist was born out of my imagination, after all. Would I no longer be perceived as a nice girl who fit well into my husband’s traditional, Catholic, mid-Western family?

My mother-in-law read the story. She complimented me on it, graciously, and when my novel came out a year ago, she wrote about it to all her friends. My father-in-law was in the hospital shortly after the novel’s release, and he bought copies for all the nurses who’d cared for him during his stay. Neither of them seem ashamed; they seemed proud.

Then again, they’re adults. My kids aren’t, quite.

The Mania of the “Best of” Lists

A Small Indiscretion has been included in the long list of 86 titles culled from the year’s finest fiction, a few of which will make the cut for the short list and be entered into Tournament of Books 2016.

I am thrilled with this news. I am grateful to whoever it was who placed me among so many authors I admire, and I am relieved not to have been overlooked. I am also dismayed that so many fine books are not on this or any other list; I am appalled that we look to lists to tell us who’s worthy, and who is not.

The post with the long list for the Tournament of Books 2016 asks readers to vote on their favorite work of fiction published in 2015, whether it’s on the list or not. Favorite, not best. That’s a step in the right direction. But when I asked myself that question–what was my favorite work of fiction published in 2015?–I was stumped.

Why? Because any book I read from beginning to end is my favorite while I’m reading it. If I’m drawn in by the voice, if I’m delighted by the sentences, if the characters feel human, if I even once pull out my pen to underline, then the book is worthwhile. And a worthwhile book will always be a favorite, because it has given me one of the most meaningful experiences of living, one unlike any other, the gift of being lost in a novel.

Asking me to choose a favorite book is like asking me to choose a favorite among my four children; they are all my favorites. Each has challenged me, surprised me, delighted me, disappointed me, made me laugh, made me cry, blessed me with immeasurable, and particular, joy.

We are a society that loves to compare, to rank, to win. There’s no way around it. But I would like to say to every single one of the writers out there who managed to pull off the improbable feat of finishing a novel and publishing it in 2015: You are a favorite. There are readers out there for whom your book mattered, not because it was the best book (there is no such thing as a best book, just as there is no such thing as a best child), but because it meant something to them personally; it moved them, it reminded them, it let them leave their own life for a little while and enter a different world. It gave them joy.

May you all have holidays full of novels and joy.

Jan